Fresh Photo Friday: Andy Goldsworthy + Beer

Staropramen, 2009

This might sound a little crazy, but I swear it’s true.

It was a hot day in Prague, the last stop on the Carleton CAMS 10-week New Media roadtrip. Professore Schott emailed us before class and told us to bring water and a sunhat, in anticipation of some unknown outdoor activity. I spent the afternoon collecting broken glass from underpasses, parks, and the riverside.

Let me explain.

In class that morning, we watched a documentary on Andy Goldsworthy, an amazing artist who produces site-specific sculptures. Our assignment for the afternoon was to “reconfigure Prague” a la Goldsworthy, and photograph the finished product. It was a competition.

Our class splintered off, each determined to capture the essence of Prague in the next two hours. I immediately took off to all the sketchy places I could think of, searching for broken beer bottles. I don’t remember much about that search, except finding some dead fish by the river. I hate dead fish.

I chose a busy bridge in Old Town to assemble and photograph my sculpture. I wanted to confront the public with the garbage I’d dragged out of corners of their city. As you can see from this photo, I got the confused looks and sidelong glances I’d been hoping for.

The next day in class, John flipped through our photos on the projector, but they were kept anonymous because of the competition. My classmates had made elaborate sculptures of cigarettes, flowers, even a video of a shadow eating lunch, but I liked my chances.

Our judge was a dashing art professor named Otto who led a weekend trip to Moravia for our class.

Yes, really.

The judging finally took place on Sunday afternoon. We were on our way back to Prague and had stopped for a lazy picnic by a scenic lake. A few of us were wading in the shallow water, half-liter bottles of beer in our hands when Otto casually called for us to hear the results of our competition. He leaned easily against a tree, polarized sunglasses and a black-collared shirt completed his bad-ass mystique. Otto announced the runners-up. I tried to keep it cool but I was nervous. Then he was saying, “and ze vinner, ze one vith ze glass and bottle. It vas very nice.” I stepped out of the lake to claim my prize.

So there you have it. The winner of the 2009 Carleton CAMS Roadtrip Andy Goldsworthy Prague Reconfiguration Photography Competition. I’m still not sure how to fit that into my resume.

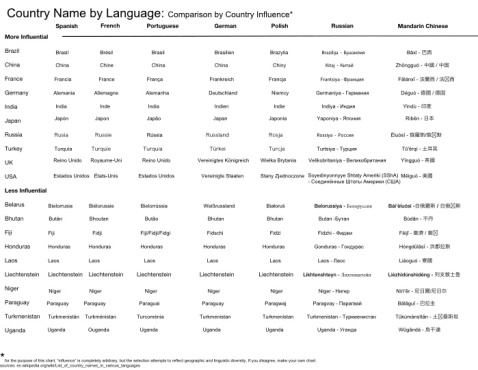

What’s in a Name: Linguistic Colonization

On my recent trip to Poland, I spent a good deal of time ogling over a map just like the one on the right.

On my recent trip to Poland, I spent a good deal of time ogling over a map just like the one on the right.

At a glance, it’s just Europe, right?

WRONG.

This map is in Polish, and a lot of the country names are pretty different, if not unrecognizable.

So this got me thinking: why are place names different in different languages?

Wouldn’t it be easier if everyone just used the same names? Think how much easier travel would be if everyone referred to Vienna as Wien. Pronunciation woes erased if Warszawa was just Warsaw.

But thankfully, the world is not so uniform or predictable.

I have a theory about this: when a language has a unique name for place or a country, people who speak said language then have a small stake in the country, a foot in the door, a piece of the nation’s pie, just for them: Linguistic colonization.

Then I started thinking about different languages, different countries and place-names. And I came up with a hypothesis: more influential countries will have a greater variety of names across languages, because a piece of their pie is tastier than less influential countries.

Then, I did an experiment. Download this pdf to follow along: CountryNamebyLanguageshort

Firstly, I’m not a linguist. There’s probably a lot more going on than what I’m observing, so I’d like to hear your thoughts on this, too.

Firstly, I’m not a linguist. There’s probably a lot more going on than what I’m observing, so I’d like to hear your thoughts on this, too.

Observations:

1.Generally, the “More Influential Countries” have a wider variety of names. They have an average of 6 significant differences across 7 languages. The “Less Influential Countries” have an average of 3.8 significant differences. (significant difference = change in spelling, not accent placements. Pronunciation plays no role here). Hypothesis proven true.

2.Look at Germany. It has 4 drastically different spellings. Only the United Kingdom and the United States also differed so drastically, and I would posit that these changes can be accounted for by the fact that their names are made up of two independent words: United and States/Kingdom. Is it possible that the roller coaster of German history and its array of incarnations (Prussia, First Reich, Weimar Republic, Third Reich, East/West Germany, United Germany, all within 150 years!) plays a role in the way it is conceptualized and referred to across languages? I think I’m on to something.

3.Honduras, Laos, Liechtenstein, Niger, Uganda boast just 2-3 variations. What’s up with that? Is it because the names just don’t translate in the languages I’m sampling? Can’t be the whole story, Honduras is definitely Spanish and Liechtenstein screams German. Or is it just that these countries aren’t important enough to these languages and their speakers to warrant a linguistic stake in their names?

I’m fascinated by this and I’d love to hear your thoughts, especially if you’re an actual linguist or a colonialist.

UPDATE:

My friend Andrew, who actually got his BA in Linguistics and is now studying at Oxford, says (via Facebook):

I feel way underqualified to answer this, but it’s so interesting! i know what you mean about random name changes. during the winter olympics in Torino different news networks used Turin (as in the shroud) or Torino. People weren’t sure if it was famous enough to use the English name or not. I think sometimes city name differences have to do with changes in pronunciation. For example, the word Rome 500 years ago would have been pronounced with two syllables by an English speaker, pretty similarly to Roma.

I like your idea about power and naming, but I’m not sure if it’s right. There are historically old names that languages have for neighboring regions, ethnic groups, or countries. It seems like different ones are used for Germany. England goes by Britain or UK and the Netherlands gets subjected to metonymy all the time when it’s called Holland, but that doesn’t have to do with power just history and government. The Chinese names are usually transliterations that get shortened. Deguo is short for Deyizhi (Deutsch) plus guo meaning country. Likewise France usually gets shortened to Faguo. America is the same too. It seems like a better way to divide names up is by language family rather than power, with proximity to the language being a factor.

I’d also say that writing systems mess everything up when moving things into new languages. sometimes people spell things the same way and then they get pronounced different ways in different places. other times, things are spelled so that they are pronounced the same but then they don’t look the same on paper. like i’d say that uganda and Fiji only have one version. although they’re spelled differently, i think that’s just as close as the languages could get either in spelling or in sound while maintaining their native phonemes.

And points interested parties to this book: Off the Map: The Curious History of Place-Names

Thanks, Andrew!

The Edge of Europe

The sun was getting low although it was only 2:30 in the afternoon, and a few of the PhDs were beginning to level their best threats at Wojciech, a Polish Geographer who had promised to get us up close and personal with the Belarus border before sunset. “If I don’t have pictures of this border, I will cut you into a thousand pieces,” the Bosnian-Italian professor told him matter-of-factly. The Israeli doctor muttered, “you’d better sharpen your knife.”

I was attending my first ever academic conference: Border Conflicts in the Contemporary World in Lublin, Poland. The last day of the event was devoted to a 12-hour excursion to Eastern Poland. All day, we had been looking at churches and cemeteries, while most of us were itching to see the actual border with Belarus, ominously nicknamed The Edge of Europe.

Finally, we piled back into the mini-bus and Wojciech announced that the next stop would be a new border crossing at Jableczna. The sun was hanging just above the horizon, but I felt pretty smug about my chances of photographing the border in low-light conditions. I was sitting in the window seat, watching the countryside of Poland D zip by. Dilapidated houses, barren fields, hardly any stores or shops. Economic ruin still reigned this far east, and it seemed oddly appropriate to find such conditions near the border, a kind of geographical gradient, a natural slide into Asia.

Suddenly, we turned a corner and nearly collided with a line of cars that stretched for at least a mile up to the border crossing. Every car was an older model, with Belorussian plates. Many of the drivers were standing outside their vehicles, smoking, chatting, drinking from thermoses. It looked like a long wait. Our purple bus flew past the line, up to the crossing point. We stopped at the first checkpoint, where Wojciech tried to sweet-talk the guard. The crossing itself loomed ahead, a huge cement gate, painted beige with cyrillic lettering, intimidating and illegible. After a few minutes the border guard told us emphatically to clear out. Do not get out, do not take pictures, do not pass go. The busload of academics griped and moaned. Nobody understands us.

Suddenly, we turned a corner and nearly collided with a line of cars that stretched for at least a mile up to the border crossing. Every car was an older model, with Belorussian plates. Many of the drivers were standing outside their vehicles, smoking, chatting, drinking from thermoses. It looked like a long wait. Our purple bus flew past the line, up to the crossing point. We stopped at the first checkpoint, where Wojciech tried to sweet-talk the guard. The crossing itself loomed ahead, a huge cement gate, painted beige with cyrillic lettering, intimidating and illegible. After a few minutes the border guard told us emphatically to clear out. Do not get out, do not take pictures, do not pass go. The busload of academics griped and moaned. Nobody understands us.

Wojciech tried to make it up to us by stopping at a border guards’ post. We were suitably underwhelmed. But the guards mentioned a nearby trail that led down to the river, the border itself. We HAD to go. By now the sun was dipping below the horizon, and we found ourselves in a hazy dusk, tramping past rusting machinery, a goat tied to a tree, and an empty field, down, down to the river. Five of us scrambled onto a sandy embankment and inhaled sharply. We were here.

Wojciech tried to make it up to us by stopping at a border guards’ post. We were suitably underwhelmed. But the guards mentioned a nearby trail that led down to the river, the border itself. We HAD to go. By now the sun was dipping below the horizon, and we found ourselves in a hazy dusk, tramping past rusting machinery, a goat tied to a tree, and an empty field, down, down to the river. Five of us scrambled onto a sandy embankment and inhaled sharply. We were here.

It was just a river, and I was thrilled by its ordinariness. There was nothing to distinguish it. The opposite bank was a stones-throw away, maybe 40 yards. We all joked about jumping in and having a go at crossing the border, and we all imagined refugees emerging from the woods at midnight, dripping wet, cold, but triumphant. But this river didn’t look different from the Canon River in my college town, where I spent lazy afternoons drifting down the current. The water here was slow. Plenty of cover. It would have been easy, I mused. Where was Fortress Europe? Where were the desperate immigrants? Where was the threat, and the protection?

It was just a river, and I was thrilled by its ordinariness. There was nothing to distinguish it. The opposite bank was a stones-throw away, maybe 40 yards. We all joked about jumping in and having a go at crossing the border, and we all imagined refugees emerging from the woods at midnight, dripping wet, cold, but triumphant. But this river didn’t look different from the Canon River in my college town, where I spent lazy afternoons drifting down the current. The water here was slow. Plenty of cover. It would have been easy, I mused. Where was Fortress Europe? Where were the desperate immigrants? Where was the threat, and the protection?

We made our way back to the bus, still parked at the guard post, generally satiated by the hike to the river. I was lingering behind and returned last to find Wojciech in an animated but polite conversation with one of the guards, encircled by our group. We piled on the bus again and Wojciech translated the discussion for the non-Polish speakers, “The guard was just asking if we had a good time and told us we could have gone to a nicer beach. We were just 50 meters away.”

We made our way back to the bus, still parked at the guard post, generally satiated by the hike to the river. I was lingering behind and returned last to find Wojciech in an animated but polite conversation with one of the guards, encircled by our group. We piled on the bus again and Wojciech translated the discussion for the non-Polish speakers, “The guard was just asking if we had a good time and told us we could have gone to a nicer beach. We were just 50 meters away.”

Oh, that’s nice.

Wait.

WHAT?

Despite the tranquility of the river, the easy current, the concealing brush, the guards had been keeping a tight rein on our little expedition. Cameras, microphones, and God-knows-what-else had been strategically planted near the border. The guard’s smirk flashed in my head; they had reason to be rather pleased. Fortress Europe is hidden, more effective than a wall, alive and well. My mind was blown, James Bond-ish fantasies satisfied, and I settled into the dark bus for a bumpy ride back to Lublin.

Notes from a Polish Train

Claustrophobia.

The car is overcrowded, and passengers linger in the hallway, hanging their heads out the window for fresh air. I find a compartment with a seat and betray myself by asking in English, “may I sit here?” No news is good news, so I plant myself between an older man who wears a suit and occupies twice the space he should, and the belongings of a young woman who stands in the aisle, smiling carefully and adjusting her hair. Everyone has stowed a suitcase, so my backpack remains on the floor in the space meant for my legs. As the train groans away from the platform and into the dark network of tracks beneath the city, my knees are already protesting their confinement.

Curiosity.

At the first stop, more people pack themselves onto the train and one seat becomes two with no small effort. I know I should expect additional passengers on the way out of town, but rarely remember to, and the newcomers have forgotten this rule of train travel as well, looking distressed by the crowding in our compartment. Suddenly, two women decide to seek their fortunes elsewhere on the train. The giant man who just arrived can now sit opposite me and I can breath deeply again. I reach into my pocket for my iPod with newfound elbow room as I appraise him out of the corner of my eye. He wears a checkerboard flannel shirt, yellow and black, and smells faintly of labor and sweat. He is graying reluctantly and his face is deeply lined, topography that speaks silently of years. He sits restlessly, eyes closed with his head in his hands, hunched under some invisible load. My imagination casts him as a woodcutter, returning home from some unknown errand. He answers two phone calls. He helps a girl with her suitcase. He wears no wedding band. I cannot guess his business on this foggy night.

Companions.

Our train is slow, slow enough to examine the graffiti at each dingy station we pass, lit by unfaithful fluorescent lights. But none of these platforms is the right one and the journey drags on, further east than I have ever been with each passing kilometer. There are three students in my compartment. One diligently reads a chemistry book in the corner, fixated and unmoving, except to turn pages. Another writes steadily, page after page of Polish script. The other listens to electronic music loud enough for all of us to hear while browsing a magazine. She wears a tank top with sequins and periodically pulls mysterious things from her purse. I always feel a vague kinship with anonymous travel companions as we find ourselves sharing space and a destination. But I never express this, instead I make up stories and personalities for the people I find on trains, crammed in a 6 by 4 compartment, and planes, somehow brought together at 35,000 feet. It’s a fleeting connection, a weak spell that is broken upon safe arrival. Finally, the chemist stops reading, the introverted writer puts away her journal, the fashionista packs up her bag, and the woodcutter snaps awake and rises to his full height. We have arrived. The doors of the train open with a hiss and like a horde of ants, its passengers emerge, streaming into the orange glow of street lamps and mist without looking back.