Nova Scotia’s Cold War

I recently remembered a geographical oddity I’ve been meaning to write about. Last summer, I led bike trips around Nova Scotia’s southern coast. On the eastern side, north of Liverpool, we passed through two tiny villages named East Berlin and West Berlin.

My group was coming from the east and if I recall correctly, there is a hill between East Berlin and West Berlin, and I encouraged my young charges by telling them we were escaping the East German communist regime on a particularly scenic road to freedom. I’m not sure if any of them found this truly motivating, but I was fascinated by the villages’ namesakes and eager to learn more about their history.

Unfortunately, I haven’t found any information on the villages (aside from how to get a vacation rental there), so I can only speculate. A few observations and questions:

1. There are lots and lots of towns in Nova Scotia named after more famous European cousins (i.e. Liverpool). It’s entirely conceivable that German immigrants settled on the coast and named their new home after their former capital.

2. Surely, these unfortunate names must have been bestowed before the German division and the Cold War. How did East Berlin and West Berlin residents feel in the light of these developments? Did East Berlin real estate prices plummet?

3. Here’s the kicker: West Berlin used to be named Blueberry, according to a sign at the entrance to the village. When did they change it and why? Does it reflect a desire to connect with their neighbors, or to distinguish themselves from the East Berliners? Maybe the mayor was allergic to blueberries? Perhaps there was a berry blight?

4. A little investigation on Google Maps reveals a West Berlin in New Jersey, and East Berlins in Pennsylvania and Connecticut; the latter lies east of a larger Berlin. But as far as I know, this partnership in Nova Scotia is one-of-a-kind.

Have you been to East Berlin and West Berlin, Nova Scotia? Can you explain the history behind these village names? Accident of history, or too good to be a coincidence?

On Permanence

My latest fascination related to European history and borders is embodied by this video:

There are a couple things that really strike me here:

1. The fluctuation on the British Isles. Scotland, Ireland, and Wales alternate between independence and being sucked up by England’s imperial gravity over the course of the video.

2. The long fragmentation of ‘Germany’, particularly as other nation-states become larger and seemingly more unified around it.

3. The amazing music choice, somehow making 1000 years of European war and conquest more dramatic than it already is.

But these are just minor observations. What I really want to talk about is the last 20 seconds of the video, the last 70 years it represents, and how we understand the permanence of borders.

So go back and watch the last part, starting after World War II where the purple of Nazi Germany is squeezed off the map. After this there is a minor shake-up, and then, calm. For the three-second period that represents the Cold War,nothing changes. This is astonishing after having watched the European map morph unrecognizably for the last three minutes. At 3:16, the Iron Curtain falls, the Soviet Union collapses, and Eastern Europe gets rearranged, while Western Europe remains still. Overall, this 70-year period from World War II to the present day sees significantly fewer fluctuations of borders and territory than almost any other 70-year period throughout the rest of the video.

In the long view, 70 years is not much time, and the medium of the timelapse illustrates this perfectly, giving equal weight to each year as an impartial observer. My lived history, the German division that gets my heart racing and my fingers reaching for the pause button, the Nazi occupation which looks so terrifying on this screen, are all treated equally, as the format cannot understand or accommodate which events resonate with its viewers, which movement of lines and colors changed lives. It is the combination of this equality inflicted by the medium, and the familiarity of the last 70 years by virtue of the human lifespan, which makes this period stand out and demand special consideration.

Europe has become an ‘easy’ place to travel, a summer destination for college students and retirees alike, comfortable, peaceful, and relatively well-off.

It’s easy to forget that this is a new development for a weary continent.

When we learn geography, it’s too often from the perspective of “this is how things are” not “this is how things are…for now.” My lifetime alone has seen the fall of the Soviet Union, the dawn of the European Union, Hong Kong’s transfer of sovereignty, the construction of the Israeli Separation Barrier, South Sudan’s secession, the rise (and fall?) of the economic borders of the Eurozone. And despite this, I still have an overwhelming, gut reaction to regard current borders as the Alpha and Omega of political geography, because stuff like this feels real:

But my fascination with borders comes from the inevitable yet improbable changes they undergo, physically, mentally, geographically, politically. It’s easy to forget that these changes happen at all when you’re standing at the base of a 30-foot wall. But this timelapse of European borders reminds me that these changes happened both 1000 years ago and in my lifetime, and in all likelihood, they will happen again, for better or worse. Changing borders requires daily work, maybe a watershed moment, but also patience to remember the long view and appreciate the passage of time, because stuff like this is real, too:

This Place

Since I got my first map of Nicosia last week, I’ve been fascinated by how Cypriots visually conceive of their cities and country. My map, as well as other representations, usually highlight the division, but also do not show any detail on the other side of the Buffer Zone. It’s blank space, uncharted, unknown, and unimportant. The discourse is everywhere, from official maps to graffiti on the street. I’m working on a series that explores and documents this theme.

The Edge of Europe

The sun was getting low although it was only 2:30 in the afternoon, and a few of the PhDs were beginning to level their best threats at Wojciech, a Polish Geographer who had promised to get us up close and personal with the Belarus border before sunset. “If I don’t have pictures of this border, I will cut you into a thousand pieces,” the Bosnian-Italian professor told him matter-of-factly. The Israeli doctor muttered, “you’d better sharpen your knife.”

I was attending my first ever academic conference: Border Conflicts in the Contemporary World in Lublin, Poland. The last day of the event was devoted to a 12-hour excursion to Eastern Poland. All day, we had been looking at churches and cemeteries, while most of us were itching to see the actual border with Belarus, ominously nicknamed The Edge of Europe.

Finally, we piled back into the mini-bus and Wojciech announced that the next stop would be a new border crossing at Jableczna. The sun was hanging just above the horizon, but I felt pretty smug about my chances of photographing the border in low-light conditions. I was sitting in the window seat, watching the countryside of Poland D zip by. Dilapidated houses, barren fields, hardly any stores or shops. Economic ruin still reigned this far east, and it seemed oddly appropriate to find such conditions near the border, a kind of geographical gradient, a natural slide into Asia.

Suddenly, we turned a corner and nearly collided with a line of cars that stretched for at least a mile up to the border crossing. Every car was an older model, with Belorussian plates. Many of the drivers were standing outside their vehicles, smoking, chatting, drinking from thermoses. It looked like a long wait. Our purple bus flew past the line, up to the crossing point. We stopped at the first checkpoint, where Wojciech tried to sweet-talk the guard. The crossing itself loomed ahead, a huge cement gate, painted beige with cyrillic lettering, intimidating and illegible. After a few minutes the border guard told us emphatically to clear out. Do not get out, do not take pictures, do not pass go. The busload of academics griped and moaned. Nobody understands us.

Suddenly, we turned a corner and nearly collided with a line of cars that stretched for at least a mile up to the border crossing. Every car was an older model, with Belorussian plates. Many of the drivers were standing outside their vehicles, smoking, chatting, drinking from thermoses. It looked like a long wait. Our purple bus flew past the line, up to the crossing point. We stopped at the first checkpoint, where Wojciech tried to sweet-talk the guard. The crossing itself loomed ahead, a huge cement gate, painted beige with cyrillic lettering, intimidating and illegible. After a few minutes the border guard told us emphatically to clear out. Do not get out, do not take pictures, do not pass go. The busload of academics griped and moaned. Nobody understands us.

Wojciech tried to make it up to us by stopping at a border guards’ post. We were suitably underwhelmed. But the guards mentioned a nearby trail that led down to the river, the border itself. We HAD to go. By now the sun was dipping below the horizon, and we found ourselves in a hazy dusk, tramping past rusting machinery, a goat tied to a tree, and an empty field, down, down to the river. Five of us scrambled onto a sandy embankment and inhaled sharply. We were here.

Wojciech tried to make it up to us by stopping at a border guards’ post. We were suitably underwhelmed. But the guards mentioned a nearby trail that led down to the river, the border itself. We HAD to go. By now the sun was dipping below the horizon, and we found ourselves in a hazy dusk, tramping past rusting machinery, a goat tied to a tree, and an empty field, down, down to the river. Five of us scrambled onto a sandy embankment and inhaled sharply. We were here.

It was just a river, and I was thrilled by its ordinariness. There was nothing to distinguish it. The opposite bank was a stones-throw away, maybe 40 yards. We all joked about jumping in and having a go at crossing the border, and we all imagined refugees emerging from the woods at midnight, dripping wet, cold, but triumphant. But this river didn’t look different from the Canon River in my college town, where I spent lazy afternoons drifting down the current. The water here was slow. Plenty of cover. It would have been easy, I mused. Where was Fortress Europe? Where were the desperate immigrants? Where was the threat, and the protection?

It was just a river, and I was thrilled by its ordinariness. There was nothing to distinguish it. The opposite bank was a stones-throw away, maybe 40 yards. We all joked about jumping in and having a go at crossing the border, and we all imagined refugees emerging from the woods at midnight, dripping wet, cold, but triumphant. But this river didn’t look different from the Canon River in my college town, where I spent lazy afternoons drifting down the current. The water here was slow. Plenty of cover. It would have been easy, I mused. Where was Fortress Europe? Where were the desperate immigrants? Where was the threat, and the protection?

We made our way back to the bus, still parked at the guard post, generally satiated by the hike to the river. I was lingering behind and returned last to find Wojciech in an animated but polite conversation with one of the guards, encircled by our group. We piled on the bus again and Wojciech translated the discussion for the non-Polish speakers, “The guard was just asking if we had a good time and told us we could have gone to a nicer beach. We were just 50 meters away.”

We made our way back to the bus, still parked at the guard post, generally satiated by the hike to the river. I was lingering behind and returned last to find Wojciech in an animated but polite conversation with one of the guards, encircled by our group. We piled on the bus again and Wojciech translated the discussion for the non-Polish speakers, “The guard was just asking if we had a good time and told us we could have gone to a nicer beach. We were just 50 meters away.”

Oh, that’s nice.

Wait.

WHAT?

Despite the tranquility of the river, the easy current, the concealing brush, the guards had been keeping a tight rein on our little expedition. Cameras, microphones, and God-knows-what-else had been strategically planted near the border. The guard’s smirk flashed in my head; they had reason to be rather pleased. Fortress Europe is hidden, more effective than a wall, alive and well. My mind was blown, James Bond-ish fantasies satisfied, and I settled into the dark bus for a bumpy ride back to Lublin.

Mapping the Contemporary Iron Curtain

Last winter, an intern at Facebook created the above graphic, which represents ten million “friendships” on the social networking site with a thin blue arc connecting the real world locations of the users. The result was astonishing. By plotting this data, Paul Butler created a recognizable world map, which displayed not only Facebook friendships, but also continents, oceans, and countries. Paul wrote about the project and commented, “What really struck me, though, was knowing that the lines didn’t represent coasts or rivers or political borders, but real human relationships.” Yet, a cursory inspection of the map is enough to realize that the lines often DO imitate political boundaries. Although they do not represent borders themselves, the Facebook map reinforces their presence and significance in our lives, which is perhaps more profound than we realize.

Look at this map carefully and you can clearly see the shadow of East Germany in a significantly less-dense field of Facebook users. This map suggests that despite our increasingly globalized civilization, political borders still determine the way we live, work, and socialize in a way that is self-perpetuating. By examining a variety of contemporary maps, it will become clear that although the Iron Curtain fell 21 years ago, it is still a deeply felt reality beyond the traditional political map of Europe.

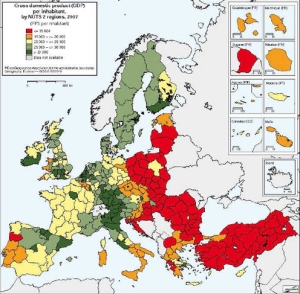

Consider this map of Europe (above) during the Cold War and compare it against the subsequent maps. You’ll see startling similarities.

Contemporary Maps and Statistics

The most startling examples are economic. Unemployment is higher, and income is lower almost across the board in areas once behind the Iron Curtain. Most strikingly, note the presence of our phantom East Germany, sharply distinguished from its western counterpart in each map.

Internet access and broadband connections in households

Internet access and broadband connections in households

The map to the left is about internet access, and how prevalent it is an given region. Again, notice the significant gap behind the Iron Curtain. This statistic seems like the odd man out, but is likely rooted in the economic struggle Eastern Europe faced under Communist rule, and the subsequent discrepancy in technological and industrial development. It also goes a long way toward explaining our Facebook graphic-it’s difficult to have online friendships when you don’t have internet access.

Pupils at primary and lower-secondary education, as a percentage of total population

Here’s another off-topic statistic: countries once behind the Iron Curtain are more likely to have a lower percentage of their population in school at the primary and lower-secondary levels. What does this mean? There are fewer young people in the East. Especially, less young, educated people. The problem of young talent fleeing the East was a large factor in the construction of structures like the inner-German border and the Berlin Wall. It continues to plague these regions today, and the trend will probably continue as long as GDP and economic well-being (and internet access!) is at stake. And this time, there’s no physical border to stop them, only this invisible one, which lures migrants across.

It’s also important to note that there are a lot of maps and statistics from Eurostat that DO NOT show any sort of lingering east/west divide. These include things as diverse as: farming structure, transport infrastructure, and fatal diseases of the respiratory system. And, many statistics can be attributed to things like climate that are much larger than any political border.

However, the maps and the data they represent suggest that overall, Eastern Europe, specifically countries that were east of the Iron Curtain, are still behind their Western counterparts, economically and technologically. Furthermore, it is the lingering effect of Europe’s division that is to blame. Quite frankly, many people would not find it surprising that countries like Poland, Belarus, even the Czech Republic are a bit behind. Yet, the repeated appearance of the phantom East Germany on these maps is strong evidence that the gap is directly related to the Iron Curtain and its continued legacy.

The Recession and Conclusions

This issue has been dragged into the spotlight in European responses to the recent recession. As bailouts and debt were first hotly debated in 2008, Hungarian Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany and Czech Prime Minister Mirek Topolanek both voiced their fears of a new divide in Europe. Their countries’ economies are struggling, yet they desperately wish to avoid more debt owed to Western Europe. Gyurcsany actually invoked the term “iron curtain” while Topolanek warned against “new dividing lines” and a “Europe divided along a North-South or an East-West line.” Unsurprisingly, the recession hit hardest in weak economies once behind the Iron Curtain. As the Eurozone struggles to pull itself together, it’s increasingly difficult to ignore this touchy fact.

What can we learn from these maps?

- The Iron Curtain lives on as an economic and social gap between East and West Europe and remains tied to an identifiable place on the map.

- Political borders go way deeper than bureaucracy and citizenship. They permeate all aspects of economics, society, daily life, and will continue to do so long after their demise.

- Is the gap self-perpetuating? When considering the data represented in the above maps in conjunction with the Facebook graphic, it’s easy to make the case that the Iron Curtain has spilled into a younger generation, despite the march of globalization. If this is true, it’s hard to predict when its legacy will no longer negatively impact the present day economics and overall well-being of Eastern Europe, especially in under the pressure of a global recession that threatens the stability of the European Economic Union.